Due to the recent results of Sight & Sound's Top 50 Greatest Films I've found myself compelled to revisit various films; to reanalyse the stature and appeal of some regarding their placing on the list, with others due to the desire to experience timeless examples once again. Whereas I need no encouragement to come back to The Passion Of Joan Of Arc, or Vertigo time and time again, I felt drawn to Renoir's The Rules Of The Game to decide for myself whether it deserves the title of '4th greatest film of all time' - a title also making it the 'greatest French film of all time'. Upon second viewing I believe it does deserve its newly confirmed status as such; though the allegorical insight into French bourgeoisie morals on the eve of World War II may be harder to decipher when viewed today, it certainly hasn't lost any of its marvel due to the widening scope of this fine film's vision. Working as a comedy of manners, a doomed love story, and satire to the upper classes; The Rules Of The Game can be enjoyed on any of these levels. What took me aback this time was just how fresh the film feels, the dialogue is rich and naturalistic while never dull for a second. Renoir's direction is also a wondrous achievement with his voyeuristic fluid camera observing events in a stylised fashion but one which never takes away from character and story. His composition (making great use of the expansive rooms which the characters occupy) manages to be both impressive but never distracting, the mark of a masterful director. The fact that The Rules Of The Game is a top 10 staple of most critics, directors, and scholars is of no surprise due to its historical insights, technical innovation, and lasting entertainment.

A Man Escaped (1956, Robert Bresson)

One of the most important films from one of the most important directors ever. Having noted and respected the sheer impact of Bresson's film while studying for my degree, I was hardly moved by it at all on first viewing. Maybe this was due to seeing it as a standalone with no prior knowledge or exposure to Bresson's work, as his films are most rewarding when viewed within the context of an auteur. When you understand where he's coming from artistically, when you learn about his background and key concerns, then you unlock the key to why he's so heavily regarded as one of the finest filmmakers to ever have lived. A Man Escaped - like all of Bresson's work - is stripped of all artifice but contain so much more than meets the eye, this simple but true tale of a French resistance fighter's elaborate escape from a POW camp during WWII can be viewed in many ways depending on the spectator. For me, it's a tale of redemption and the difficult (as well as lonely) path to salvation, but what is often forgotten in Bresson's work is his command of suspense, a vital ingredient that A Man Escaped utilises with great effect. Perhaps the lack of applause for Bresson's knack for thrillers stems from his intensely minimalist and almost non-cinematic style, though no one can make a case for his work lacking any cinematic splendour with the displays of rich photography and use of music (here Mozart's Great Mass in C Minor). As we follow our protagonist planning day in day out the means to an escape, despite learning nothing of his character or backstory, or even what he's been imprisoned for, you connect with his situation. Bresson's withholding of information and naturalistic performances has us project ourselves onto his characters; at one point our 'hero' is told he will be executed the next morning, not sure whether he'll be moved to another room thus making his plans and effort after all these months ineffectual and leading him to certain death, the suspense has your heart stop beating as his does. A Man Escaped is just one of many praised works by Bresson but it's with this film that he's most known within the history of cinema, perhaps his ever developing style coupled with relatable material (based on the memoirs of POW Andre Devigny, Bresson was also captured during wartime) made for a lasting masterpiece, one with a lasting effect still felt today.

Pickpocket (1959, Robert Bresson)

The second film of Robert Bresson I watched this week, though the thrills and transcendent nature of A Man Escaped once again confirmed said film a masterpiece, I sadly can't say the same for Pickpocket. Widely considered one of Bresson's better films and certainly one of his most influential, I could only see its lasting legacy on cinema without seeing any appeal or cause for appraisal. This slight updating of Dostoevsky's Crime & Punishment follows a young thief, his philosophies on a Darwinism of sorts, and the detective closing in on him. While Bresson's cinema is one of a minimalist quality, Pickpocket felt devoid of any connection whatsoever. The decision to apply Dostoevsky's tale to a smalltime (yet skilled) thief loses all weight when compared to Raskolnikov's murderer, also the casting of non-actor Martin LaSalle as thief Michel is problematic due to his vapid screen presence, offering no engagement to make concern for his future possible. The much needed chemistry between LaSalle and female (romantic) lead is also gravely lacking. Though early scenes showing Michel's thefts are well handled suspenseful examples that go in the film's favour, all is lost by the time Pickpocket reaches halfway through its mere 75minute runtime. Pickpocket is interesting when viewed on the merit of its lasting influence as without it we perhaps wouldn't have Taxi Driver, its resemblance to Christopher Nolan's low-budget debut Following (1998) is also apparent, and for this alone Pickpocket has more than earned its keep.

Une Femme Est Une Femme (1961, Jean-Luc Godard)

Godard's first foray into colour in which he uses his new palette as if it's going out of fashion. The most joyous and accessible of his work, Une Femme Est Une Femme follows Angela (played by a never more lovely Anna Karina) a striptease artist desperate for a baby. Boyfriend Emile (Jean-Claude Brialy) is against the idea and as the couple continue to argue he says half-heartedly that she should seek assistance from his friend Alfred (Jean-Paul Belmondo) if a baby means that much to her. Emile, not realising the extent to which Angela will go to, nor that his best friend is in love with her, sets himself up for a fall in his ignorance and insensitive manners. Godard never allows the plot to ever become heavier than a grain of salt though, yet he manages to include insights into adult relationships without ever taking us aside to announce them. The playful tone of the film has much to do with Godard's homage and deconstruction of the musical and romantic comedy genres, Godard's experimental editing technique and bold use of music keeps you on your toes throughout with its oddball effects showcasing the frustrating genius of the director. The sight of Anna Karina playacting pregnancy in front of the mirror with an obscenely large cushion cracks me up every time, seeing Brialy continue to argue while riding a bike in the living room is just another example of how childish Godard's characters are. Perhaps this is the film's main point, that as we grow older and take on important adult decisions our childish pettiness (and selfishness) still remain, that an adult is merely a child with more layers. A perfect place to start when exploring the cinema of Anna Karina, her many collaborations with (then lover, later husband) Godard, and as well as the timeless À bout de souffle (1960) the best place to being with Godard's work in general. At one point during the film Angela is asked what she's thinking, she replies, "I'm thinking that I exist", after Une Femme Est Une Femme is through you'll certainly be thankful she does.

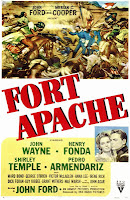

Fort Apache (1948, John Ford)

The only film I've watched this week that doesn't happen to be French is John Ford's Fort Apache; the first part of Ford's 'Calvary Trilogy', the tale matches two screen icons and Ford regulars in a battle of ego and alpha male showmanship. Henry Fonda plays a Lieutenant Colonel Owen Thursday - a general of The Civil War who's higher command have transferred him to manage the Fort Apache post which John Wayne's Captain Kirby York was expected to take control of. What transpires is a test of honour as Thursday's lack of experience with the Apache Indians puts their operation in peril, York has the experience and the respect of the fort's men to carry their duty out successfully and must face up to the stone wall of his new commander. It's a fun adventure with laughs and romance (Shirley Temple plays Thursday's plucky daughter) with a brilliant supporting cast and a rare icy performance from Fonda who plays the grudge baring Thursday to perfection. Despite the fact that Ford made black & white masterpieces such as Stagecoach (1939) and The Grapes Of Wrath (1940), I've always felt that his pictures took on new levels once he utilised colour; here his beloved Monument Valley lacks that mythic quality in monochrome, the setting for all his westerns. The fact that Fort Apache feels like rather minor Ford is testament to the man's legacy and tremendous body of work he left behind, because the film really is a great entertainment that pitches two of Hollywood's finest screen actors against each other. Ford, Fonda, Wayne, how can you say no to that any day of the week?

Watch of the week: With its joyous tone, ridiculous humour, and gorgeous photography and set design, my pick of the week goes to Une Femme Est Une Femme. I so wanted to say The Rules Of The Game but with Anna Karina's seductive fluttering eyelashes it just didn't seem possible after all.

Une Femme Est Une Femme is wonderful! Great choice! x

ReplyDelete